In early January 2025, blogger Rashad Ramazanov, recognized as a political prisoner, voiced the harsh conditions in Penitentiary Institution No. 15, where he was being detained. In his exclamation, the prisoner mentioned that sanitary regulations were violated in the institution in question, the rules for the detention of prisoners were not followed, and there were numerous problems with their nutrition.

Given that these claims require extensive legal analysis, “Tribunat” platform will present two different articles. The first one – the one you are currently reading – deals with the difficulties associated with the legislative regulation and practical implementation of food provision in prisons.

Ramazanov, in his complaint, indicates that the food served to prisoners in the prison is of poor quality. Per his words, prisoners are restricted from receiving alternative food from home, and the prices of food in the store operating within the institution are expensive.

Similar allegations are constantly being made by other detainees (temporary detention places and pre-trial detention centers) and prisons, both in the media and to domestic and international legal protection mechanisms.

The legislation of the Republic of Azerbaijan recognizes the right of detainees in both places of detention and penitentiary institutions to be provided with quality meal three times a day. According to Article 20 of the Law “On Ensuring the Rights and Freedoms of Persons in Places of Detention”, Article 10.8 of the “Internal Disciplinary Rules of Temporary Detention Places” and Article 11 of the “Internal Disciplinary Rules of Pre-trial Detention Centers”, detainees in pre-trial detention centers and places of temporary detention are provided with free, hot meals three times a day, in accordance with the nutrition, material and household standards established by the Cabinet of Ministers, and in terms of quality, meeting modern hygiene requirements and dietary standards. A similar provision applies to prisoners serving their sentences in general, strict, special regime penitentiary institutions and prisons, in accordance with Article 91.4 of the Code of Execution of Sentences and Article 338 of the “Internal Disciplinary Rules of Penitentiary Institutions”.

These norms are progressive in nature, they not only ensure the quality of food for individuals, in addition, in relation to places of detention, require that the age, health status and religious traditions of the individual be taken into account during meals. This is directly consistent with Article 22 of the European Prison Rules, which regulates nutrition issues (the said article determines the organization of meals prepared in accordance with sanitary and hygienic requirements, taking into account the age, health, religion, culture and nature of the work of the prisoner).

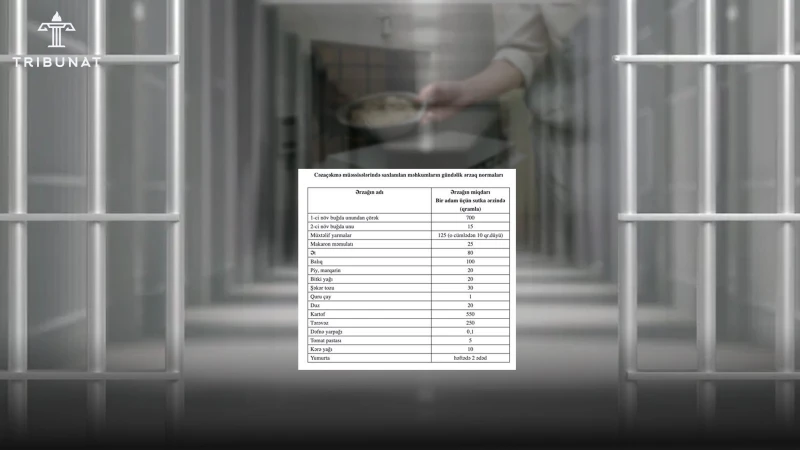

The decisions adopted to ensure the practical implementation of these laws and regulations (Decision No. 22 of the Cabinet of Ministers of February 18, 2013 “On Approval of Nutrition and Material Standards for Detainees or Arrested” in relation to those held in places of detention, and Decision No. 154 of September 25, 2001 “On Approval of Nutrition and Material Standards for Convicts” in relation to penitentiary institutions) regulate food provision more specifically and determine the daily consumable meal norms.

It is somewhat difficult to affirm progressive nature of said provisions as the norms mentioned above.

Hence, even though the rules stipulate the amount of products such as meat, fish, eggs, pasta, potatoes, vegetables, and fruits to be provided to convict and detainees, the meals are not accompanied by variety (which means that prisoners are given the same food every day), the quantity of some foods is small (for example, only two eggs are given to a prisoner per week), or some products that would meet a person's essential nutritional needs are not provided for at all (for instance, these rules do not cover the provision of prisoners with dairy products). The rules are harsher in prisons, where the kilocalorie content of meals is lower than in places of detention, and they do not include products such as fruit and juice, which could provide prisoners with essential vitamins in addition to essential nutrients. Moreover, none of the rules themselves reflect a variety of choices and almost always require prisoners to eat the same foods every day.

Alternatively, detainees and convicts are allowed to purchase food products from trading kiosks using funds in their personal accounts through non-cash payments. The allegations suggest that prices at trading kiosks are quite expensive. Although the law stipulates a list of products that can be sold at trading kiosks, their price limits are not regulated. This leads to a monopoly of the said kiosks in determination of prices.

Another problem is the determination of the maximum amount of money that prisoners can spend on food and essential goods (this limit is not set for detainees held in pre-trial detention centers and temporary detention centers). In accordance with the Code of Execution of Sentences, prisoners can purchase these goods only up to a certain amount, depending on the type of prison. For instance, a person convicted of less serious crimes serving a sentence in a general regime prison can spend up to 50 manats per month on food and essential goods, while if he is held in prison, this amount equals to only 25 manats. As observed, these amounts are quite small and may allow for the purchase of only a small number of products from a trading kiosk where bread costs 1 AZN.

In accordance with Appendix No. 6 of the “Internal Disciplinary Rules of Temporary Detention Places”, Appendix No. 2 of the “Internal Disciplinary Rules of Pre-trial Detention Centers” and Appendix No. 9 of the “Internal Disciplinary Rules of Penitentiary Institutions”, detainees have the right to receive additional parcels, gifts or packages. Nonetheless, the law also establishes several restrictions in that regard. Initially, the law puts forward the frequency of delivery of packages. Hence, a convict can receive a parcel, gift or package once a week, while a detainee can receive a parcel, gift or package every day. In penitentiary institutions, depending on the type, a prisoner can receive at most 48 parcels, gifts or packages per year, and in other cases this number does not exceed 24. Convicts held in prisons can receive only 6 parcels, gifts or packages per year, and in strict detention conditions - 1 parcel, gift or package every six months.

The scope of the gifts that can be brought is also limited. Only 9 types of products can be brought by their families to arrested and imprisoned persons, which excludes many products, including uncooked meat, fish, pasta and pasta products, rice, corn, peas and other legumes.

According to the data by Council of Europe for 2023, Azerbaijan is the third country in the region in terms of the proportion of people imprisoned following Turkey and Georgia, with 235 prisoners per hundred thousand people in the country. Nonetheless, Azerbaijan is the country that spends the least on prisoners per capita. According to the Council of Europe's Annual Penal Data, the budget allocated for one person imprisoned in Azerbaijan in 2023 was 8.24 euros. For comparison, this figure is 29 in neighboring Armenia, 167.57 in Austria, 230 in Ireland, 15.30 in Georgia, and 12.45 euros for Turkey.

As observed, there are various gaps in the penitentiary legislation. Yet, another problem is related to the implementation of the legislation. The most important of these allegations is related to the quality of food received by prisoners. Sevinj Vagifqizi, the detained editor-in-chief of AbzasMedia, stated in her public appeal that since the food in the detention center is of poor quality, only 8 out of 27 cells receive it. By her, only 4 pieces of meat were given to a cell for 14 people in the Baku Pre-Trial Detention Center. Interestingly, a similar situation was identified not only by the political prisoners themselves and their families, but also by the Commissioner for Human Rights (Ombudsman). The Ombudsman's Report on the Activities of the National Preventive Mechanism Against Torture for 2022 reflected that some food was of poor quality, that gifts were not allowed into the detention center, and that food was sold at expensive prices in kiosks. The Ombudsman also indicates the abovementioned issue - the fact that the cafeteria menu has not changed for a long time - and recommends that establishments increase the variety on the menu.

The nutrition problems faced by prisoners in both pre-trial detention centers and prisons have been the subject of three separate applications to the European Court of Human Rights against Azerbaijan (Insanov v. Azerbaijan, Aliyev v. Azerbaijan, and Yunusova and Yunusov v. Azerbaijan). In Insanov, the applicant complained that he was not provided with food suitable for his health. In Aliyev, the applicant alleged that the food provided in the pre-trial detention center was of poor quality and that he was entirely dependent on his family for nutrition (Aliyev, §47). The detention facility does not have a refrigerator and he was only able to receive a food parcel from his family once a week. In the Yunusova and Yunusov, the applicant, in addition, complained that he was not being provided with food appropriate to his state of health. The Court, which did not comment on this issue in Insanov (presumably because it was preoccupied with other more pressing matters), stated in Yunusova and Yunusov that, even though it was clear that the applicants had been following a diet given the nature of their illnesses, the Government had not specified what food the applicants were being provided with in detention. Generally, there is no indication in the case that the applicants’ conditions of detention were adapted to their state of health. In Aliyev, the Court clearly stated that there were many allegations in the case concerning the conditions of detention and that, for the sake of brevity, it would only examine the issue of overcrowding (§123). In each of these three cases, the Strasbourg Court, taking into account the cumulative conditions of detention, found that the applicants' right to be free from torture under Article 3 of the Convention had been violated and concluded that they had been subjected to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Resultantly, the current situation with regard to food provision in places of detention and penitentiary institutions is caused by both gaps in the legislation and practical issues. Even though the legislation aims to ensure the right to food for prisoners in a broad sense in accordance with Article 22 of the European Prison Rules, some norms do not meet modern requirements and the diet of a healthy person and create restrictions on alternative food intake. Whereby, the condition of a variety of nutrition is not required, the amount of some foods such as eggs, which are a daily necessity, is in small quantities or does not provide for the provision of fruits and dairy products that are important for human health, the upper price limit for goods sold in shopping stalls is not determined by law, monetary limits are set for the amount that prisoners can spend, etc. Simultaneously, serious problems and violations are observed in the implementation of existing rules, which further complicates the conditions of detention of prisoners.

Nutrition-related problems, combined with the general quality of detention conditions, seriously violate the rights of prisoners and give grounds to conclude that they are subjected to inhuman or degrading treatment. Therefore, it is important to both close the gaps in the legislation and strengthen the practical implementation of the laws in order to improve the current situation.