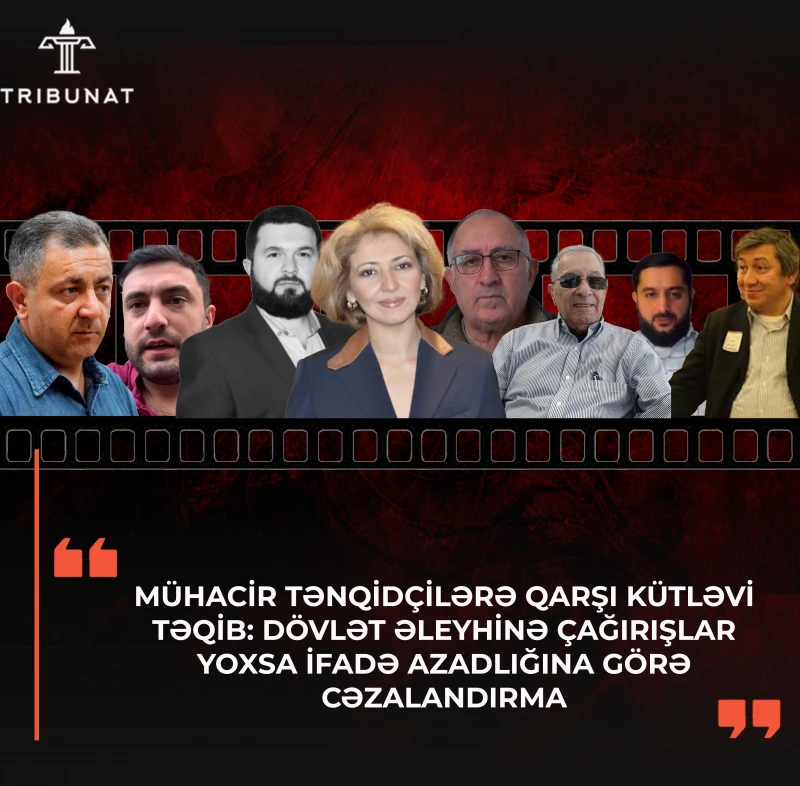

In November of this year, several bloggers, journalists, and public figures living abroad were summoned to the Prosecutor General's Office. Among them are journalist Sevinj Osmangizi, public activists Abid Gafarov, Vagif Allahverdiyev, political commentator Beydulla Manafov, Murad Guliyev, historian Altay Goyushov, political scientist Arastun Orujlu, and blogger Manaf Jalilzade. The common thread that unites the aforementioned individuals is that they were found guilty under Article 281 of the Criminal Code (hereinafter, CC) (the public appeals directed against the state).

“Tribunat” analyzed Article 281 of the CC, the legality of the accusations of the aforementioned individuals, and the interaction of the accusations with freedom of expression.

Article 281 of the CC is aimed to punish actions directed at the forcible seizure of power, forcible retention, or forcible amendment of the constitutional structure of the Republic of Azerbaijan or the disintegration of its territorial integrity, as well as the dissemination of materials with such content.

In accordance with the Commentary to the CC, appeals should be understood as active actions aimed at influencing the will of people and attracting them to commit the acts specified in this article.

The listed charges should be interpreted as a logical continuation of the in absentia proceedings initiated against critics living abroad (you can read more about in absentia proceedings in this article). The persecution of such critics, supported by officials, has already resulted in the initiation of court proceedings and the sentences in absentia against certain individuals.

The aforementioned individuals participate in various Internet resources, mainly on the video hosting platform “Youtube”, either as authors (for instance, Sevinj Osmangizi) or as experts, organizing discussions on issues covering the socio-political agenda. Information obtained from open sources allows them to investigate the content that forms the basis of the accusations made.

For instance, one of the episodes in which political scientist Arastun Orujlu is accused refers to the video clip “What has the past year taught us” published on the “Arastun Orujlu’s channel” YouTube channel on January 4, 2023. Hereby, the topic covers the discussion of socio-political events on the agenda for 2022, mainly the events known as the “Tartar case/incidents” and involving the mass torture and murder of servicemen accused of spying for Armenia in 2017. A. Orujlu states that in order to achieve justice for the victims, “it is necessary to fight and use social media correctly.” Then, upon discussion of foreign policy issues, he accuses the current government of “not being interested in protecting national interests” and “plundering the resources and wealth of the people and the country.” Finally, Orujlu calls on viewers of the video to “expose those who commit injustices and atrocities”.

One of the episodes attributed to Sevinc Osmangizi is a video clip titled “Why does the consulate put 50 Azerbaijanis in front of 5,000 Armenians?” published on the “OSMANGIZI TV” YouTube channel on July 25, 2020. The author comments on the riots between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in the state of California of the United States of America, in July 2020. Against the background of what happened, she accuses the Azerbaijani consulate of being the cause of the threat to the lives and safety of ethnic Azerbaijanis, saying that they were not properly protected.

One of the episodes in which the critic immigrant Abid Gafarov was accused concerns a video titled “Abid Gafarov: Can there be such a state? 28.4.24” that was aired on April 29, 2024, on the “AzerFreedom TV” YouTube channel, owned and hosted by lawyer Gurban Mammadov, who lives as an immigrant in London. Gafarov, along with Mammadov and 3 other individuals, discuss agenda topics related to the “Tartar case” and criticize the investigation conducted by state bodies and the general reaction and attitude shown. Specifically, A. Gafarov discusses his novel “Andaluniya”, which is "dedicated to the horrors of Tartar events". He then criticizes the public for lack of reaction to the facts of mass torture against military personnel. In conclusion, Gafarov comments on the restrictions and obstacles he encountered in the publication and distribution of the book, addressing state institutions, "You are not persecuting drug dealers, not pimps, but book sellers, is this what a state would be like?"

It is not clear from the information disseminated in the media which of the acts constituting the objective aspect of the criminal offense provided for in Article 281 of the CC were committed by the accused. Following review of the episodes that substantiate the accusation, it is possible to express reasonable doubts regarding the formation of the criminal offense of the mentioned episodes, based on the CC and its Commentary. Conditionally, let us single out several characteristic elements:

1. Public appeals against the state;

2. Dissemination of such content;

3. Influencing the will of people;

4. Vigorous actions aimed at attracting them to commit such acts.

It implies that the statements of the accused must openly voice actions that will contradict the existing constitutional structure of the state (provocation, diversion, sabotage, riots, etc.), incite to this and significantly influence the will of those who will follow them. The public appelas mentioned in the disposition of the article, however, do not imply the contextual nature of these statements, but rather the existence of instructions that encourage the implementation of active actions. When considering the mentioned episodes, the impression arises that law enforcement agencies use criminal prosecution to punish the interpretation and discussion of socio-politically important issues, not the actions constituting the crime.

There is a long history of abuse of Article 281 of the CC by investigative bodies in Azerbaijan. The list of political prisoners prepared by the Institute for Peace and Democracy for October this year includes 11 people convicted of public appeals directed against the state. The list includes party functionaries, ethnic minority activists, bloggers, social media users, and immigrants.

But how do domestic courts define such “open appeals”? It is possible to see from media monitoring and Supreme Court decisions that there are problematic moments in this context as well. For instance, in the criminal case against journalist Anar Mammadov, who commented on the assassination attempt on the former head of the executive power of Ganja, Elmar Valiyev, one of the facts proving the existence of “open appeals” for law enforcement agencies and the court was that three women, including a former police officer, were “excited” by Mammadov’s writings. Despite the fact that the accused and his advocate complained about the absence of witnesses in the trial and the political motivation of the case, A. Mammadov was sentenced to 5 years and 6 months in prison by the Baku Court of Grave Crimes on March 18, 2019.

Another example concerns Elvin Isayev, a critical blogger in exile. Isayev was deported from Ukraine to Azerbaijan on December 12, 2019, as part of criminal proceedings initiated by the Prosecutor General’s Office against him on charges of public appelas against the state. In connection with the preventive measure of pre-trial detention selected based on the decision of the Nasimi District Court dated August 22, 2019, he was placed in the Baku Investigative Detention Center of the Penitentiary Service on December 14. The reason for the deportation was Isayev’s violation of Ukrainian migration legislation. According to reports, the basis of the accusation was Isayev's videoblogs titled “Idols will be overturned” and “How long will those living abroad remain silent?”. Resultantly, E. Isayev was sentenced to 8 years in prison by the Baku Grave Crimes Court on October 31, 2020. In consideration of the above, the description of the speeches in this context as “public appeals against the state” raises reasonable questions.

It can also be observed from the decisions of the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court dated 07.12.2021, No. 1(102)-1792/2021, dated 22.02.2022, No. 1(102)-4/2022, and dated 22.08.2023, No. 1(102)-1340/2023 that law enforcement agencies rely on the statements of the accused and witnesses and the results of linguistic expertise as evidence of public appeals against the state. The problematic points highlighted by the accused regarding the charges - that they were forced to testify against themselves through inhumane treatment, that the statements constituting the crime described the current situation on the subject and did not incite violence, that the expert opinions were unfounded, incomplete and repetitive, and that the two first instance courts did not objectively assess the evidence - were not commented on by the Supreme Court.

The above-mentioned points contradict the obligations of the court and law enforcement agencies to provide evidence in criminal proceedings. According to Article 145 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, each piece of evidence must be assessed for its relevance, possibility, and reliability. The totality of all evidence collected in criminal proceedings must be assessed based on its sufficiency for the resolution of the charge. By the Code, sufficiency means such a volume of possible evidence in the circumstances to be determined that would allow a reliable and conclusive conclusion to be drawn for the determination of the subject of proof. The problematic points mentioned in the above examples do not provide grounds for a reliable and conclusive conclusion that the accused committed acts constituting a crime.

The misuse of this charge against critics violates the right to freedom of opinion and expression, as protected by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. According to the Convention, “everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers and to receive and impart information and ideas.” The Convention recognizes this right as a relative, not an absolute, right, the exercise of which may in certain cases be subject to such formal requirements, conditions, restrictions or sanctions as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society.

The “prescribed by law” standard includes not only the fact that a restriction is laid down in legislation, but also the relevant specific elements, and most importantly the quality of the law. In accordance with the Court’s case-law, in particular in criminal proceedings which may sanction freedom of expression, legislation must prevent the list of acts punishable by the Government from being too broad and subject to abuse through selective use (Savva Terentyev v. Russia; §85).

One of the main purposes of freedom of opinion and expression protected by Article 10 is to protect the interests and benefits of civil society actors (media, NGOs, activists, etc.), which the Court has interpreted as “public watchdogs” (Taner Kılıç v. Turkey (no. 2), §147). Where such “media” freedom is considered, the Government’s margin of appreciation must be interpreted more narrowly (Stoll v. Switzerland; §85). Individuals must have freedom of choice in the sharing of their information and views. The Court has noted that it is not for the ECtHR or a domestic court to interfere in determining what information individuals share, how and in what manner (Jersild v. Denmark; §31).

By the way, so far, in 22 cases against Azerbaijan, the European Court has ruled that the Government violated the rights of individuals and legal entities protected by Article 10 of the Convention.

Hence, law enforcement agencies that define the charge of open calls against the state in a broad and arbitrary manner unreasonably restrict the freedom of thought and expression of the relevant individuals. It is also possible to see from the examples that these charges are intended not to protect public values protected by criminal law, but to punish individuals who express information and opinions on sensitive issues.

“Tribunat” concludes that the charge of public incitement against the state is applied to immigrant critics in a manner inconsistent with domestic and international law. This constitutes a restriction on freedom of expression and leads to a “chilling effect.” The arbitrary and unlawful application of such punishment is common in domestic practice.